Day One Hundred Two

I woke up in the middle of the night to Jessica trying to worm her way under my covers. I knew I should comfort her but was too tired to do more than scoot over and go back to sleep. In the morning, I found her spooned up against me, clutching her doll. She felt me moving around and opened her eyes.

“Was there something wrong with your room?” I asked.

“It was dark.”

“It was dark in here, too.”

She said nothing, pulling the blanket up to her chin and staring at me.

“It’s nice to have your company,” I said. “But you’re going to have to learn how to sleep in your own room after I leave.”

“Where are you going?”

I figured she wouldn’t know anything about Kentucky. “My new home. A very nice place with green hills and horses.”

“I want to go.”

“Don’t be silly. You’re staying here with Grandma.”

“Grandma doesn’t like me.”

“Don’t say that. Of course she likes you. It’s just that your mommy was her baby, and she’s sad just like you are. I bet if you give her a hug this morning, you’ll find out if she likes you or not. Just one hug, okay?”

It took a little cajoling, but I convinced Jessica to give it a try. Then I got dressed, found Jessica some clean clothes to wear, and braided her hair. When we got downstairs, Mrs. Keller was sitting at the kitchen table staring into a cup of coffee but not drinking any. Jessica looked up at me for encouragement, then went to the woman and flung herself against her. “Good morning, Grandma.”

Mrs. Keller was startled, but then pulled the girl into her lap and held her close. I thought she was going to cry. Instead she kissed the top of her head, wished her a good morning and asked what she wanted for breakfast.

“Pancakes.”

“I think we can do that.”

“I’ll make breakfast,” I offered. “That way you don’t have to get up.”

“No, nothing’s going to keep me from making breakfast for my sweet girl.” She stood up awkwardly because of her leg and settled Jessica into the chair with another kiss.

At Mrs. Keller’s urging, I poured myself a cup of coffee and sat down while she mixed up a bowl of batter. She got around pretty well on her crooked leg. Sometimes she used her cane and other times she hobbled the short distances between counters and chairs that she used for support.

The first pancake was already cooking when the boys trooped into the kitchen, looking remarkably tidy, their hair slicked down with water. I figured David must have taken some initiative with Jeremy and I promised myself that I would compliment him on it later.

Breakfast was delicious and the children behaved themselves. The boys were still uncertain what they thought of their grandmother, but now that Jessica had decided Grandma was okay, things were less formal than they had been the night before. I think Mrs. Keller is one of those cautious people who doesn’t show affection easily. Having lost her daughter doesn’t help. But time will draw this family closer. Soon they won’t even remember that they had once felt unsure of each other.

After breakfast I went upstairs to pack my bags. I was nearly finished when I heard a slow thumping on the stairs, followed by Mrs. Keller’s wobbling steps down the hallway. She tapped on my door and since I hadn’t closed it all the way, it swung open. She paused in the doorway, looking at my bags. “You know,” she said, “You’re welcome to stay as long as you like.”

“That’s very nice of you, but I need to be on my way. I’m going to Kentucky, and I still have a long way to go.”

“What’s in Kentucky? Family?”

“I don’t know anyone there. I just like the idea of it.”

She eased herself into a chair. “Stay here. The children seem to like you, and there’s plenty of room. You would be just like kin.”

It was a generous offer, and I’m sure she meant every word she said. But I’m not dumb. With no daughter to support her and the children, she was hoping I might make a suitable substitute. And if I didn’t have other plans and thought I could find a job, it would’ve been a good offer. But what would I do for work? Join another gang, like I had when Ishkin was in the hospital in January? No, I wasn’t going to do that sort of thing again, if I could help it. And the sad truth was that I had no real city skills. No one needed the sort of work I was trained to do. Not here. But in Kentucky, with all those horse farms. . .

I shook my head. “Thank you. It means a lot to me to hear you say that. But I’m not a city girl, and I have other plans.”

She left to make up the children’s beds, and I finished packing. Then on a sudden inspiration, I took a knife and began ripping open the seams of my jacket. Necklace chains, small coins, jeweled earrings and a ring fell out. Tanner’s stolen goods. I scooped everything into a small pile and examined it. It wasn’t so much, really. It would be just a drop in the bucket of what it would cost Mrs. Keller to raise three children alone. But maybe she could rent out the room I was in now. The boys could share a room, making another room available to rent. David could probably do small jobs around the neighborhood, and. . .

Oh, why was I worrying about it? It wasn’t my problem. I found a handkerchief in a dresser drawer and tied up Tanner’s fortune in it, enclosing a note that simply said, “For the children.” I slipped it under my pillow where I knew Mrs. Keller would find it later.

Leaving was hard. The children didn’t want me to go. Jeremy and Jessica cried, and David stood stoically with such a look of betrayal on his face that I felt like I was committing a crime. “Be good and mind your grandma,” I told them. “I’ll write, okay? And maybe some day you can visit me in Kentucky.”

I got a few last-minute bits of travel advice from Mrs. Keller, and then I was on my way. I couldn’t bear to look back.

I rode for several blocks without paying attention to where I was going. But when I turned onto a busier street, I was forced to look around and get my bearings. This wasn’t a very big city. There had been some suburbs on the way in, but this older area was where most people lived and worked now. The buildings seemed more solid here, and everyone looked busy. The presence of soldiers reminded me once again that I was in the United States. They rode horses like policemen did, and sometimes a group of them would pass by in a diesel truck. These scared me, reminding me of the trucks that brought the soldiers to Valle Redondo. I would be glad to get out of the city.

But first I needed supplies. I still had a little money and a few gold chains that Vince had given me two months ago. So I found a store and went inside, curious as to what kinds of good they would have, and what they would cost. I wished now that I had kept some of my federal money, but I had never known anyone to refuse gold or silver. For the price of a few silver coins, I was able to get wheat flour, beef jerky, cow cheese, pecans, dried peaches, and some nuts called peanuts.

Feeling rich in edible goods, which is the main reason to have money anyway, I got back onto the city streets and tried to get my bearings.

I wandered around under one of those elevated roads called freeways, which only the military seemed to be using, and finally found the road Mrs. Keller had told me about. It was noon and I was way behind schedule, but I was heading northeast again.

It didn’t take as long as I had feared to get beyond the city. Soon I was in open country, and Flecha seemed as happy as I was to be back where we belonged. She tossed her head and tugged at the bit, so I let her trot for awhile, both of us enjoying the spring afternoon. There were some sad-looking people on the road, refugees searching for better places and better times, and there were heavy merchant wagons lumbering along, too. But I tried to ignore it all and just take pleasure in being out in the sunshine.

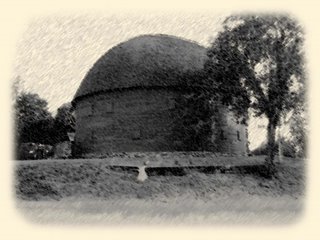

Around late afternoon, deeper into the countryside now, we came upon a remarkable sight.

I had never seen anything like it in my life. I was so curious, that I peeked in the open door and asked the old man inside what was the meaning of a round barn.

“It’s a special design,” he explained. “It was quite the tourist attraction at one time, but it’s a working barn again these days. The whole village uses it.”

“Village?” I had seen a few houses nearby, but they hadn’t looked habitable.

“There’s a few families here, yet. We aren’t all dead.”

I asked a few more questions about the barn, and the man said that if I would help him bring in the cows, he would show me how it worked. I hadn’t ever handled cows, but I figured it couldn’t be too hard. I unloaded my packs so Flecha could maneuver better, and together me and the old man, who said his name was Marshall, drove the cows in from pasture. I think I was more trouble than help, but the milk cows were docile, so no great harm was done.

The cows went into the barn, where their stalls all faced inward, in a circle. At the center of the circle was a sort of empty column, and hay could be dropped down from above where it would be available to all. It was really smart, and I wondered aloud at the sort of person who would think of such a design. Everything about the barn was beautiful, even the roof beams.

Since by now it was growing dark, Marshall invited me to stay for supper. He lived alone, but his cabin was tidy and he had been simmering a pot of beans all day and they were pretty good. He offered to let me sleep on his living room floor, but I asked if I could sleep in the barn, instead. He laughed like I was crazy, but said to go ahead.

What fun! I made up a bed of hay near Flecha, and covered it with my tarp and blankets. I can’t see the wheel of the roof beams overhead in the dark, but I know they’re there like an enormous star. How wonderful that one can find something so amazing in a practical old barn! The United States is nice, and so are its people. I’m glad this is my country. When I get to Kentucky, maybe I’ll join Unitas again, if they won’t make me fight. I want to help my people back home become part of the USA again. Just like those orphaned children needed to be with their grandmother, we all need to stick together.

◄ Previous Entry

Next Entry ►

“Was there something wrong with your room?” I asked.

“It was dark.”

“It was dark in here, too.”

She said nothing, pulling the blanket up to her chin and staring at me.

“It’s nice to have your company,” I said. “But you’re going to have to learn how to sleep in your own room after I leave.”

“Where are you going?”

I figured she wouldn’t know anything about Kentucky. “My new home. A very nice place with green hills and horses.”

“I want to go.”

“Don’t be silly. You’re staying here with Grandma.”

“Grandma doesn’t like me.”

“Don’t say that. Of course she likes you. It’s just that your mommy was her baby, and she’s sad just like you are. I bet if you give her a hug this morning, you’ll find out if she likes you or not. Just one hug, okay?”

It took a little cajoling, but I convinced Jessica to give it a try. Then I got dressed, found Jessica some clean clothes to wear, and braided her hair. When we got downstairs, Mrs. Keller was sitting at the kitchen table staring into a cup of coffee but not drinking any. Jessica looked up at me for encouragement, then went to the woman and flung herself against her. “Good morning, Grandma.”

Mrs. Keller was startled, but then pulled the girl into her lap and held her close. I thought she was going to cry. Instead she kissed the top of her head, wished her a good morning and asked what she wanted for breakfast.

“Pancakes.”

“I think we can do that.”

“I’ll make breakfast,” I offered. “That way you don’t have to get up.”

“No, nothing’s going to keep me from making breakfast for my sweet girl.” She stood up awkwardly because of her leg and settled Jessica into the chair with another kiss.

At Mrs. Keller’s urging, I poured myself a cup of coffee and sat down while she mixed up a bowl of batter. She got around pretty well on her crooked leg. Sometimes she used her cane and other times she hobbled the short distances between counters and chairs that she used for support.

The first pancake was already cooking when the boys trooped into the kitchen, looking remarkably tidy, their hair slicked down with water. I figured David must have taken some initiative with Jeremy and I promised myself that I would compliment him on it later.

Breakfast was delicious and the children behaved themselves. The boys were still uncertain what they thought of their grandmother, but now that Jessica had decided Grandma was okay, things were less formal than they had been the night before. I think Mrs. Keller is one of those cautious people who doesn’t show affection easily. Having lost her daughter doesn’t help. But time will draw this family closer. Soon they won’t even remember that they had once felt unsure of each other.

After breakfast I went upstairs to pack my bags. I was nearly finished when I heard a slow thumping on the stairs, followed by Mrs. Keller’s wobbling steps down the hallway. She tapped on my door and since I hadn’t closed it all the way, it swung open. She paused in the doorway, looking at my bags. “You know,” she said, “You’re welcome to stay as long as you like.”

“That’s very nice of you, but I need to be on my way. I’m going to Kentucky, and I still have a long way to go.”

“What’s in Kentucky? Family?”

“I don’t know anyone there. I just like the idea of it.”

She eased herself into a chair. “Stay here. The children seem to like you, and there’s plenty of room. You would be just like kin.”

It was a generous offer, and I’m sure she meant every word she said. But I’m not dumb. With no daughter to support her and the children, she was hoping I might make a suitable substitute. And if I didn’t have other plans and thought I could find a job, it would’ve been a good offer. But what would I do for work? Join another gang, like I had when Ishkin was in the hospital in January? No, I wasn’t going to do that sort of thing again, if I could help it. And the sad truth was that I had no real city skills. No one needed the sort of work I was trained to do. Not here. But in Kentucky, with all those horse farms. . .

I shook my head. “Thank you. It means a lot to me to hear you say that. But I’m not a city girl, and I have other plans.”

She left to make up the children’s beds, and I finished packing. Then on a sudden inspiration, I took a knife and began ripping open the seams of my jacket. Necklace chains, small coins, jeweled earrings and a ring fell out. Tanner’s stolen goods. I scooped everything into a small pile and examined it. It wasn’t so much, really. It would be just a drop in the bucket of what it would cost Mrs. Keller to raise three children alone. But maybe she could rent out the room I was in now. The boys could share a room, making another room available to rent. David could probably do small jobs around the neighborhood, and. . .

Oh, why was I worrying about it? It wasn’t my problem. I found a handkerchief in a dresser drawer and tied up Tanner’s fortune in it, enclosing a note that simply said, “For the children.” I slipped it under my pillow where I knew Mrs. Keller would find it later.

Leaving was hard. The children didn’t want me to go. Jeremy and Jessica cried, and David stood stoically with such a look of betrayal on his face that I felt like I was committing a crime. “Be good and mind your grandma,” I told them. “I’ll write, okay? And maybe some day you can visit me in Kentucky.”

I got a few last-minute bits of travel advice from Mrs. Keller, and then I was on my way. I couldn’t bear to look back.

I rode for several blocks without paying attention to where I was going. But when I turned onto a busier street, I was forced to look around and get my bearings. This wasn’t a very big city. There had been some suburbs on the way in, but this older area was where most people lived and worked now. The buildings seemed more solid here, and everyone looked busy. The presence of soldiers reminded me once again that I was in the United States. They rode horses like policemen did, and sometimes a group of them would pass by in a diesel truck. These scared me, reminding me of the trucks that brought the soldiers to Valle Redondo. I would be glad to get out of the city.

But first I needed supplies. I still had a little money and a few gold chains that Vince had given me two months ago. So I found a store and went inside, curious as to what kinds of good they would have, and what they would cost. I wished now that I had kept some of my federal money, but I had never known anyone to refuse gold or silver. For the price of a few silver coins, I was able to get wheat flour, beef jerky, cow cheese, pecans, dried peaches, and some nuts called peanuts.

Feeling rich in edible goods, which is the main reason to have money anyway, I got back onto the city streets and tried to get my bearings.

I wandered around under one of those elevated roads called freeways, which only the military seemed to be using, and finally found the road Mrs. Keller had told me about. It was noon and I was way behind schedule, but I was heading northeast again.

It didn’t take as long as I had feared to get beyond the city. Soon I was in open country, and Flecha seemed as happy as I was to be back where we belonged. She tossed her head and tugged at the bit, so I let her trot for awhile, both of us enjoying the spring afternoon. There were some sad-looking people on the road, refugees searching for better places and better times, and there were heavy merchant wagons lumbering along, too. But I tried to ignore it all and just take pleasure in being out in the sunshine.

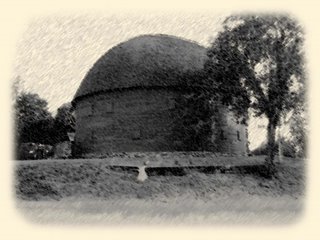

Around late afternoon, deeper into the countryside now, we came upon a remarkable sight.

I had never seen anything like it in my life. I was so curious, that I peeked in the open door and asked the old man inside what was the meaning of a round barn.

“It’s a special design,” he explained. “It was quite the tourist attraction at one time, but it’s a working barn again these days. The whole village uses it.”

“Village?” I had seen a few houses nearby, but they hadn’t looked habitable.

“There’s a few families here, yet. We aren’t all dead.”

I asked a few more questions about the barn, and the man said that if I would help him bring in the cows, he would show me how it worked. I hadn’t ever handled cows, but I figured it couldn’t be too hard. I unloaded my packs so Flecha could maneuver better, and together me and the old man, who said his name was Marshall, drove the cows in from pasture. I think I was more trouble than help, but the milk cows were docile, so no great harm was done.

The cows went into the barn, where their stalls all faced inward, in a circle. At the center of the circle was a sort of empty column, and hay could be dropped down from above where it would be available to all. It was really smart, and I wondered aloud at the sort of person who would think of such a design. Everything about the barn was beautiful, even the roof beams.

Since by now it was growing dark, Marshall invited me to stay for supper. He lived alone, but his cabin was tidy and he had been simmering a pot of beans all day and they were pretty good. He offered to let me sleep on his living room floor, but I asked if I could sleep in the barn, instead. He laughed like I was crazy, but said to go ahead.

What fun! I made up a bed of hay near Flecha, and covered it with my tarp and blankets. I can’t see the wheel of the roof beams overhead in the dark, but I know they’re there like an enormous star. How wonderful that one can find something so amazing in a practical old barn! The United States is nice, and so are its people. I’m glad this is my country. When I get to Kentucky, maybe I’ll join Unitas again, if they won’t make me fight. I want to help my people back home become part of the USA again. Just like those orphaned children needed to be with their grandmother, we all need to stick together.

◄ Previous Entry

Next Entry ►

1 Comments:

I'm amazed she managed to pull her self away form the kids so gracefully. Leaving the booty behind for them was a nice touch.

Post a Comment

<< Home