Day One Hundred One

Children are impossible!

This morning, the two younger ones decided that we needed to go back to the bridge! I know they’re grieving and confused. I’ve been trying to think what it would’ve been like for me if I hadn’t actually seen my mother and grandparents die, and if I hadn’t had bodies to bury. I suppose if it hadn’t all been so irrevocably real, I would’ve wanted to stay in the valley in the mad delusion that my loved ones might reappear one day. So I sympathize with these children. But sympathy doesn’t get a person to Oklahoma City.

How do parents resist the temptation to dose their children with corn whiskey and hog-tie them? It’s no wonder Catherine seemed depressed.

So I did the only thing I could think to do. After breakfast, I took David aside. “You’ve got to help me,” I said. “I know you’re sad and angry. I saw my mother murdered by soldiers when I was your age, so I know what you’re feeling. But you’re the head of the family now. The children will listen to you. Are you enough of a man to help get them to your grandmother’s? You’re not still a little boy, are you?”

My appeal to every child’s wish to be grown up had a good effect. David squared his shoulders. “I can do it.”

“Good. Remember, we can’t be mean to them. They’re just children. But we also can’t indulge any foolishness. If all goes well, we should be able to get there by tonight.”

David adopted a serious demeanor and frowned, a little furrow forming between his brows. He was really trying to be grown up. And then he surprised me with an idea so obvious I felt stupid for not having thought of it myself. “Why don’t we tell them that we think Mother is already at Grandma’s, waiting?”

I would’ve hugged him if I hadn’t been afraid it might damage his fragile first steps at being an adult.

So that’s what we did. It was a terrible lie to tell, but the road is no safe place for children. Fighting them, it would’ve easily taken two more days to get to Oklahoma City. With their eager compliance, everything changed. They ate what I gave them, helped load the wagon, didn’t fight over who sat where, and didn’t even complain about the noise and jostling of the wagon rims on the broken asphalt. I carried Jessica on the saddle with me sometimes to give her a break from the bouncing wagon, but Jeremy stuck close to his brother on the seat. I could tell that David was still angry with him, but he was doing his best to control his feelings. “You can spend the whole rest of your life hating him,” I had told him before we left the cottage, “But just for today, pretend like everything’s all right. Hate him tomorrow, okay?”

The trip was going pretty well, and I was beginning to think I could make out the smudge of a city on the horizon, when we came upon a lake and a crisis occurred.

“Is that where Mommy is?” Jessica asked, pointing toward the water.

Before I could answer, Jeremy said, “Yes, the river brought her here.”

I started to explain that the river she had fallen into didn’t come to this lake, but David solved the problem by stating, “Yes, the river carried her here. But she’s already gotten out and gone to Grandma’s. We need to hurry up.”

“How do you know?” Jeremy asked. “We should go look.”

“It’s only a little farther to Grandma’s,” I told him. “We’ll go there, first, and come back if we need to.”

What a hassle cities are! But I remembered what I had learned the last time I was in a city and pointed to the tall buildings in the distance. “We’ll go toward the buildings. That’s downtown, and from there, we can get directions.”

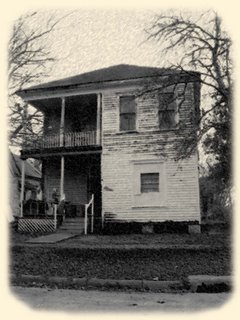

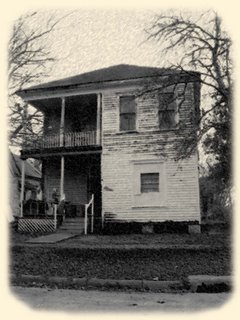

From a distance, the downtown area looked pretty good. I wondered if maybe things were better here in the United States than at home, and they were still able to use those old buildings made out of glass, steel, and concrete. But as we got closer, we saw that a lot of the windows were broken out. The only buildings that were occupied were the shorter ones from at least a hundred and fifty years ago—the ones with windows that opened so one could get proper ventilation without electricity. We stopped at one of these buildings, and I went inside and showed a few people the address on Catherine’s letters, until I finally found someone who could give me directions that made sense.

Even so, it wasn’t easy to find the place. Street signs had been taken down by metal thieves, and the replacement signs of wood were in some cases missing or turned around so that we got lost a few times and had to ask again for help. But finally we found what appeared to be the right house.

David halted the wagon and I jumped down from my horse and went over to him. He looked at me wide-eyed, his earlier show of confidence crumbling. “It’s only an old lady,” I told him. “And she wants to be nice to you. You can be brave for that, can’t you?”

“It’s just I don’t know her.”

“None of us do. We’ll have to be brave together, won’t we?” I patted the gun at my side. “Just yell if she tries to bite. I’ve got you covered.”

This made him laugh, and we got the two younger children onto the sidewalk where I tried to smooth their hair and wrinkled clothing. But before we could go to the door and knock, it flew open and a woman came hobbling down the steps toward us. She had that white-streaked black hair called salt-and-pepper, and she walked with a cane. But the cane seemed to be because of a leg deformity and not old age, because she moved fast. She was in front of us before we knew it, smiling in pleasant confusion at the children and then at me. Her eyes returned over and over to the wagon, looking for someone else.

I sucked in my breath. “Mrs. Keller?”

She nodded.

“These are your grandchildren. David, Jeremy and Jessica.”

Her smile broadened as she looked at them, but she made no move to touch them. Instead, she turned puzzled eyes on me. “Who are you? I thought my daughter. . .”

“Let’s get the children inside. They’ve had a long trip, and they’re tired.”

“I want to see Mother!” Jeremy blurted out.

Mrs. Keller and I locked eyes. I guess she read something in my face that hinted at the truth, because she turned to Jeremy. “How about you come inside and let me fix you some supper? I’ve been expecting you, and I have a surprise.”

I could tell that no surprise short of their mother waiting in the living room was going to quiet the children for long. As we went inside, I pulled David back. “Keep the children distracted,” I said. “She already knows something’s not right, so it won’t take long to explain.”

The children’s surprise turned out to be a black and white puppy, and David did a good job keeping Jeremy and Jessica busy with it while I went into the kitchen with Mrs. Keller. We didn’t have much time, so I had to be blunt. I hope the ground swallows me whole before I ever have to tell another mother that her daughter is dead, her body’s whereabouts unknown. Mrs. Keller was brave. She’s probably seen a lot of hardship. But I swear it would’ve been easier to have fallen off that bridge myself, than to have to be the bearer of such bad news.

Supper was a thick soup made of peas and potatoes, flavored with bacon. There was wheat bread and butter to go with it. But Mrs. Keller was too upset to eat and I felt bad for being so hungry. It didn’t seem right to have an appetite while she was grieving. But she tried to put on a good face for the children’s sake, and I resisted the temptation of a second helping, even though she offered.

I was worried that the children wouldn’t want to go to bed, with the excitement of being in a new place with a new puppy, topped by the hurt and confusion of not finding their mother waiting for them. But I guess they were pretty tired after such a long journey, because after we gave them baths and put them into clean pajamas, they seemed content to be tucked into beds in rooms of their own.

There was a room for me, too—the room Catherine was to have had. But I wasn’t ready to sleep. Instead, I went with Mrs. Keller into the front room, where she poured us each a glass of wine. Then we settled into upholstered chairs that had probably once been comfortable, but were now little more than faded cloth stretched over metal springs that poked.

“Tell me everything,” she said.

So I did. I started at the beginning, with the motel in Texas, and told her every detail I could remember about what Catherine had said and done, until the moment she fell off the bridge. And then I told about the unsuccessful search for her body, and the tricks I had to play on the children to keep them docile so I could bring them here. “If you can gather some people together,” I said, “You can probably search further down the river. It’s just that there was no way for me to adequately care for the children out there, and I wanted to get them here as quickly as possible.”

“It was the right thing to do,” she said. “But I don’t have the money to send out a search party like that.”

“What would it cost?”

She made a motion with her hands. “Who knows? It would depend on how far they had to travel, and how long they were gone.” Now she shifted in her chair and gestured toward her crooked leg. “I'm poor because I can’t work much, thanks to this leg. If you ever fall and break anything, pay any price to get it set by a doctor who knows what he or she is doing. Once you’re a cripple, good luck trying to earn a living.”

“You seem to be doing okay,” I said.

“I used to have boarders, that’s why. I made them leave when my daughter asked to come home. She was going to find work and support us.”

Mrs. Keller began sniffling. She pulled a handkerchief out of her pocket, blew her nose and tried to say something else, but instead she choked on the words and buried her face in her hands. Her bravery deserted her and she began crying in earnest.

Without thinking, I got up and put my arms around her. She didn’t know me, but that didn’t seem to matter. Somehow we both ended up in that chair, with her leaning into me and sobbing like her heart had broken. It was so distressing that I found myself crying, too.

When we finally caught our breath and dried our eyes, she patted my hand. “You’re a good girl to bring me my grandchildren,” she said. “I can’t thank you enough.”

“You don’t have to thank me for doing what was right.”

She offered me a little more wine, then struggled to her feet. “You try to get some sleep, dear.”

I could tell she wanted to be alone, so I gave her an impulsive kiss on the cheek, then took my glass of wine upstairs to my room.

It’s wonderful to have a bed and a room all to myself, although it saddens me to think how it came about. This is a pretty decent little house. But without an income, I wonder how long Mrs. Keller can hold onto it? I know it’s not my problem, and people always seem to find a way. But after all the trouble of getting the children here, I had so hoped for it to be a truly happy ending. Instead, it seems like they’ve traded one set of problems for another.

◄ Previous Entry

Next Entry ►

This morning, the two younger ones decided that we needed to go back to the bridge! I know they’re grieving and confused. I’ve been trying to think what it would’ve been like for me if I hadn’t actually seen my mother and grandparents die, and if I hadn’t had bodies to bury. I suppose if it hadn’t all been so irrevocably real, I would’ve wanted to stay in the valley in the mad delusion that my loved ones might reappear one day. So I sympathize with these children. But sympathy doesn’t get a person to Oklahoma City.

How do parents resist the temptation to dose their children with corn whiskey and hog-tie them? It’s no wonder Catherine seemed depressed.

So I did the only thing I could think to do. After breakfast, I took David aside. “You’ve got to help me,” I said. “I know you’re sad and angry. I saw my mother murdered by soldiers when I was your age, so I know what you’re feeling. But you’re the head of the family now. The children will listen to you. Are you enough of a man to help get them to your grandmother’s? You’re not still a little boy, are you?”

My appeal to every child’s wish to be grown up had a good effect. David squared his shoulders. “I can do it.”

“Good. Remember, we can’t be mean to them. They’re just children. But we also can’t indulge any foolishness. If all goes well, we should be able to get there by tonight.”

David adopted a serious demeanor and frowned, a little furrow forming between his brows. He was really trying to be grown up. And then he surprised me with an idea so obvious I felt stupid for not having thought of it myself. “Why don’t we tell them that we think Mother is already at Grandma’s, waiting?”

I would’ve hugged him if I hadn’t been afraid it might damage his fragile first steps at being an adult.

So that’s what we did. It was a terrible lie to tell, but the road is no safe place for children. Fighting them, it would’ve easily taken two more days to get to Oklahoma City. With their eager compliance, everything changed. They ate what I gave them, helped load the wagon, didn’t fight over who sat where, and didn’t even complain about the noise and jostling of the wagon rims on the broken asphalt. I carried Jessica on the saddle with me sometimes to give her a break from the bouncing wagon, but Jeremy stuck close to his brother on the seat. I could tell that David was still angry with him, but he was doing his best to control his feelings. “You can spend the whole rest of your life hating him,” I had told him before we left the cottage, “But just for today, pretend like everything’s all right. Hate him tomorrow, okay?”

The trip was going pretty well, and I was beginning to think I could make out the smudge of a city on the horizon, when we came upon a lake and a crisis occurred.

“Is that where Mommy is?” Jessica asked, pointing toward the water.

Before I could answer, Jeremy said, “Yes, the river brought her here.”

I started to explain that the river she had fallen into didn’t come to this lake, but David solved the problem by stating, “Yes, the river carried her here. But she’s already gotten out and gone to Grandma’s. We need to hurry up.”

“How do you know?” Jeremy asked. “We should go look.”

“It’s only a little farther to Grandma’s,” I told him. “We’ll go there, first, and come back if we need to.”

What a hassle cities are! But I remembered what I had learned the last time I was in a city and pointed to the tall buildings in the distance. “We’ll go toward the buildings. That’s downtown, and from there, we can get directions.”

From a distance, the downtown area looked pretty good. I wondered if maybe things were better here in the United States than at home, and they were still able to use those old buildings made out of glass, steel, and concrete. But as we got closer, we saw that a lot of the windows were broken out. The only buildings that were occupied were the shorter ones from at least a hundred and fifty years ago—the ones with windows that opened so one could get proper ventilation without electricity. We stopped at one of these buildings, and I went inside and showed a few people the address on Catherine’s letters, until I finally found someone who could give me directions that made sense.

Even so, it wasn’t easy to find the place. Street signs had been taken down by metal thieves, and the replacement signs of wood were in some cases missing or turned around so that we got lost a few times and had to ask again for help. But finally we found what appeared to be the right house.

David halted the wagon and I jumped down from my horse and went over to him. He looked at me wide-eyed, his earlier show of confidence crumbling. “It’s only an old lady,” I told him. “And she wants to be nice to you. You can be brave for that, can’t you?”

“It’s just I don’t know her.”

“None of us do. We’ll have to be brave together, won’t we?” I patted the gun at my side. “Just yell if she tries to bite. I’ve got you covered.”

This made him laugh, and we got the two younger children onto the sidewalk where I tried to smooth their hair and wrinkled clothing. But before we could go to the door and knock, it flew open and a woman came hobbling down the steps toward us. She had that white-streaked black hair called salt-and-pepper, and she walked with a cane. But the cane seemed to be because of a leg deformity and not old age, because she moved fast. She was in front of us before we knew it, smiling in pleasant confusion at the children and then at me. Her eyes returned over and over to the wagon, looking for someone else.

I sucked in my breath. “Mrs. Keller?”

She nodded.

“These are your grandchildren. David, Jeremy and Jessica.”

Her smile broadened as she looked at them, but she made no move to touch them. Instead, she turned puzzled eyes on me. “Who are you? I thought my daughter. . .”

“Let’s get the children inside. They’ve had a long trip, and they’re tired.”

“I want to see Mother!” Jeremy blurted out.

Mrs. Keller and I locked eyes. I guess she read something in my face that hinted at the truth, because she turned to Jeremy. “How about you come inside and let me fix you some supper? I’ve been expecting you, and I have a surprise.”

I could tell that no surprise short of their mother waiting in the living room was going to quiet the children for long. As we went inside, I pulled David back. “Keep the children distracted,” I said. “She already knows something’s not right, so it won’t take long to explain.”

The children’s surprise turned out to be a black and white puppy, and David did a good job keeping Jeremy and Jessica busy with it while I went into the kitchen with Mrs. Keller. We didn’t have much time, so I had to be blunt. I hope the ground swallows me whole before I ever have to tell another mother that her daughter is dead, her body’s whereabouts unknown. Mrs. Keller was brave. She’s probably seen a lot of hardship. But I swear it would’ve been easier to have fallen off that bridge myself, than to have to be the bearer of such bad news.

Supper was a thick soup made of peas and potatoes, flavored with bacon. There was wheat bread and butter to go with it. But Mrs. Keller was too upset to eat and I felt bad for being so hungry. It didn’t seem right to have an appetite while she was grieving. But she tried to put on a good face for the children’s sake, and I resisted the temptation of a second helping, even though she offered.

I was worried that the children wouldn’t want to go to bed, with the excitement of being in a new place with a new puppy, topped by the hurt and confusion of not finding their mother waiting for them. But I guess they were pretty tired after such a long journey, because after we gave them baths and put them into clean pajamas, they seemed content to be tucked into beds in rooms of their own.

There was a room for me, too—the room Catherine was to have had. But I wasn’t ready to sleep. Instead, I went with Mrs. Keller into the front room, where she poured us each a glass of wine. Then we settled into upholstered chairs that had probably once been comfortable, but were now little more than faded cloth stretched over metal springs that poked.

“Tell me everything,” she said.

So I did. I started at the beginning, with the motel in Texas, and told her every detail I could remember about what Catherine had said and done, until the moment she fell off the bridge. And then I told about the unsuccessful search for her body, and the tricks I had to play on the children to keep them docile so I could bring them here. “If you can gather some people together,” I said, “You can probably search further down the river. It’s just that there was no way for me to adequately care for the children out there, and I wanted to get them here as quickly as possible.”

“It was the right thing to do,” she said. “But I don’t have the money to send out a search party like that.”

“What would it cost?”

She made a motion with her hands. “Who knows? It would depend on how far they had to travel, and how long they were gone.” Now she shifted in her chair and gestured toward her crooked leg. “I'm poor because I can’t work much, thanks to this leg. If you ever fall and break anything, pay any price to get it set by a doctor who knows what he or she is doing. Once you’re a cripple, good luck trying to earn a living.”

“You seem to be doing okay,” I said.

“I used to have boarders, that’s why. I made them leave when my daughter asked to come home. She was going to find work and support us.”

Mrs. Keller began sniffling. She pulled a handkerchief out of her pocket, blew her nose and tried to say something else, but instead she choked on the words and buried her face in her hands. Her bravery deserted her and she began crying in earnest.

Without thinking, I got up and put my arms around her. She didn’t know me, but that didn’t seem to matter. Somehow we both ended up in that chair, with her leaning into me and sobbing like her heart had broken. It was so distressing that I found myself crying, too.

When we finally caught our breath and dried our eyes, she patted my hand. “You’re a good girl to bring me my grandchildren,” she said. “I can’t thank you enough.”

“You don’t have to thank me for doing what was right.”

She offered me a little more wine, then struggled to her feet. “You try to get some sleep, dear.”

I could tell she wanted to be alone, so I gave her an impulsive kiss on the cheek, then took my glass of wine upstairs to my room.

It’s wonderful to have a bed and a room all to myself, although it saddens me to think how it came about. This is a pretty decent little house. But without an income, I wonder how long Mrs. Keller can hold onto it? I know it’s not my problem, and people always seem to find a way. But after all the trouble of getting the children here, I had so hoped for it to be a truly happy ending. Instead, it seems like they’ve traded one set of problems for another.

◄ Previous Entry

Next Entry ►

1 Comments:

I'd make the kids share a room and get more boarders in, if I were her.

So, is Diana going to go search for the body now?

Post a Comment

<< Home